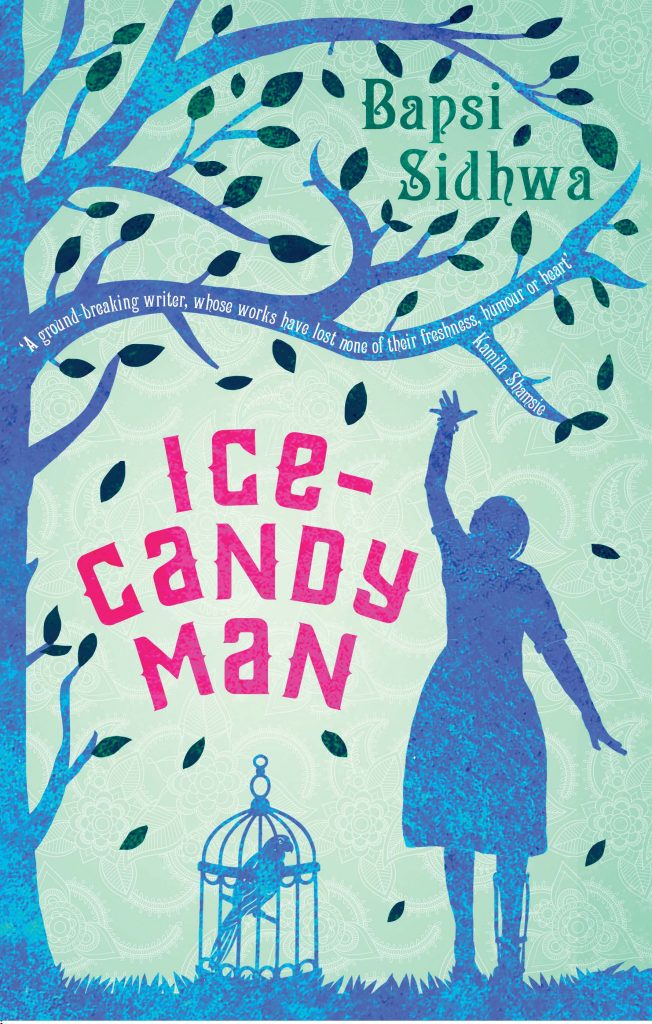

Ice-Candy Man

Posted 19th May 2016

My world is compressed. Warris Road, lined with rain gutters, lies between Queens Road and Jail Road: both wide, clean, orderly streets at the affluent fringes of Lahore.

Rounding the right-hand corner of Warris Road and continuing on Jail Road is the hushed Salvation Army wall. Set high, at eight-foot intervals, are the wall’s dingy eyes. My child’s mind is blocked by the gloom emanating from the wire mesh screening the oblong ventilation slits. I feel such sadness for the dumb creature I imagine lurking behind the wall. I know it is dumb because I have listened to its silence, my ear to the wall.

Jail Road also harbours my energetic Electric-aunt and her adenoidal son . . . large, slow, inexorable. Their house is adjacent to the den of the Salvation Army.

Opposite it, down a bumpy, dusty, earth-packed drive, is the one-and-a-half-room abode of my godmother. With her dwell her docile old husband and her slavesister. This is my haven. My refuge from the perplexing unrealities of my home on Warris Road.

A few furlongs away Jail Road vanishes into the dense bazaars of Mozang Chungi. At the other end a distant canal cuts the road at the periphery of my world.

*

Lordly, lounging in my briskly rolling pram, immersed in dreams, my private world is rudely popped by the sudden appearance of an English gnome wagging a leathery finger in my ayah’s face. But for keen reflexes that enable her to pull the carriage up short there might have been an accident, and blood spilled on Warris Road. Wagging his finger over my head into Ayah’s alarmed face, he tut-tuts: ‘Let her walk. Shame, shame! Such a big girl in a pram! She’s at least four!’

He smiles down at me, his brown eyes twinkling intolerance.

I look at him politely, concealing my complacence. The Englishman is short, leathery, middle-aged, pointy-eared. I like him.

‘Come on. Up, up!’ he says, crooking a beckoning finger.

‘She not walk much . . . she get tired,’ drawls Ayah. And simultaneously I raise my trouser cuff to reveal the leather straps and wicked steel calipers harnessing my right boot.

Confronted by Ayah’s liquid eyes and prim gloating, and the triumphant revelation of my calipers, the Englishman withers.

But back he bounces, bobbing up and down. ‘So what?’ he says, resurrecting his smile. ‘Get up and walk! Walk! You need the exercise more than other children! How will she become strong, sprawled out like that in her pram? Now, you listen to me . . .’ He lectures Ayah, and prancing before the carriage which has again started to roll says, ‘I want you to tell her mother . . .’

Ayah and I hold our eyes away, effectively dampening his good-Samaritan exuberance . . . and wagging his head and turning about, the Englishman quietly dissolves up the driveway from which he had so enthusiastically sprung.

The covetous glances Ayah draws educate me. Up and down, they look at her. Stub-handed twisted beggars and dusty old beggars on crutches drop their poses and stare at her with hard, alert eyes. Holy men, masked in piety, shove aside their pretences to ogle her with lust. Hawkers, cart-drivers, cooks, coolies and cyclists turn their heads as she passes, pushing my pram with the unconcern of the Hindu goddess she worships.

Ayah is chocolate-brown and short. Everything about her is eighteen years old and round and plump. Even her face. Full-blown cheeks, pouting mouth and smooth forehead curve to form a circle with her head. Her hair is pulled back in a tight knot.

And, as if her looks were not stunning enough, she has a rolling bouncy walk that agitates the globules of her buttocks under her cheap colourful saris and the half-spheres beneath her short sariblouses. The Englishman no doubt had noticed.

We cross Jail Road and enter Godmother’s compound. Walking backwards, the buffalo-hide water-pouch slung from his back, the waterman is spraying the driveway to settle the dust for evening visitors. Godmother is already fitted into the bulging hammock of her easy chair and Slavesister squats on a low cane stool facing the road. Their faces brighten as I scramble out of the pram and run towards them. Smiling like roguish children, softly clapping hands they chant, ‘Langer deen! Paisay ke teen! Tamba mota, pag mahin!’ Freely translated, ‘Lame Lenny! Three for a penny! Fluffy pants and fine fanny!’

Flying forward I fling myself at Godmother and she lifts me onto her lap and gathers me to her bosom. I kiss her, insatiably, excessively, and she hugs me. She is childless. The bond that ties her strength to my weakness, my fierce demands to her nurturing, my trust to her capacity to contain that trust – and my loneliness to her compassion – is stronger than the bond of motherhood. More satisfying than the ties between men and women.

I cannot be in her room long without in some way touching her. Some nights, clinging to her broad white back like a bug, I sleep with her. She wears only white khaddar saris and white khaddar blouses beneath which is her coarse bandage-tight bodice. In all the years I never saw the natural shape of her breasts.

Ice-Candy Man by Bapsi Sidhwa is published on 26th May 2016 and is available to buy now.